Geo-Mexico agrees entirely with Joseph Kerski (a key member of ESRI’s Education Team), that it is amazing “how little American students really know about their neighbor to the south.” In order to help remedy this situation, ESRI’s Witold Fraczek has created a series of online “story maps” about Mexico. The maps can be accessed in several different ways, including as an ArcGIS Online presentation and an iPad iBook, or via this webpage.

The six stories are entitled:

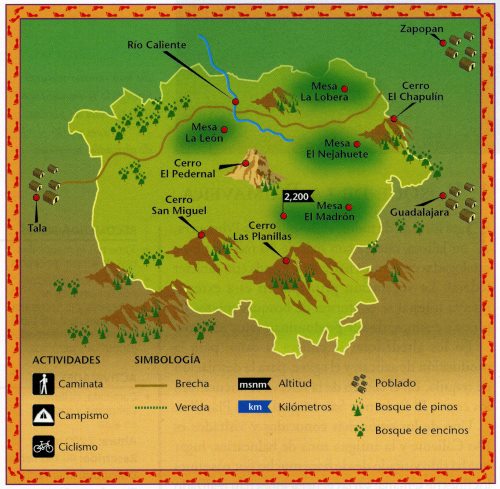

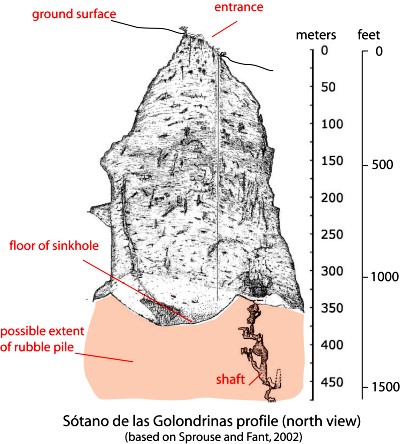

Each “story” includes several maps (covering topics such as population, landforms, climate, historical landmarks, caves, indigenous cultures, tourist attractions), some of which are interactive in the sense that clicking on a marked point brings up a pop-up panel with a photograph and/or additional information about that place. The maps, linked by short commentary notes, can be viewed at a variety of scales.

This series of maps has many strong points, and could certainly be useful in some geography classes, but it also has some weaknesses that should be taken into account when using them. Brief comments follow on each of the six stories.

1 Explore Mexico (Crime vs. Tourism)

The first map in this mini-series depicts “tourism attraction density” based on “650 major points of interest”. No clues are offered as to how the 650 points were selected, and indeed, some can not really be shown by points on a map since they cover larger areas. The map appears to weight all 650 points equally, though some are major, major tourist attractions (like the pyramids of Teotihuacan) that attract thousands of visitors a day, while others are very much less significant.

The second map, showing the “20 cities with most murders” uses data from 2011 (now out-dated) to conclude that “crime, measured by the total number of murders” appears to be “spatially isolated from the areas most attractive to tourists”. Surely murder rates (per 100,000 people) are a better measure than the number of murders in each city?

Murder rate per 100,000 is used as the basis for comparing Mexico with its regional neighbors, but Mexico is so large (and the murder rates across the country so varied) that comparisons at this scale mean relatively little, especially when some of the nations are tiny Caribbean islands, where one or two murders extra in any year can mean a significant spike in their murder rate.

2. Mexico’s Natural Wonders

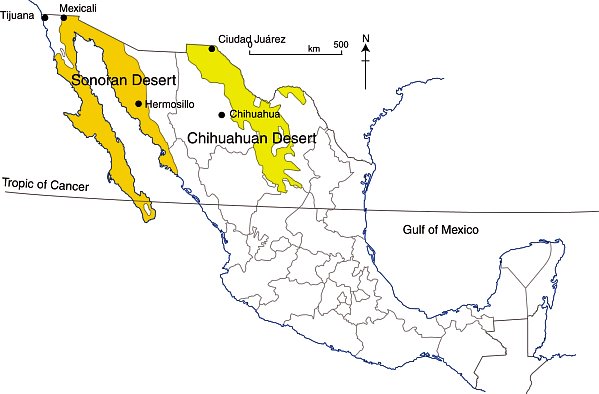

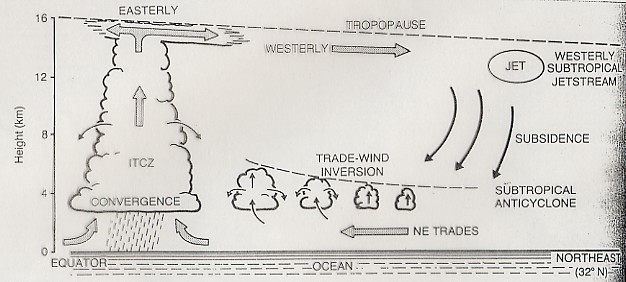

The introductory text to this section rightly highlights how “the natural world of Mexico varies amazingly, from tropical jungles and coral reefs to deserts and glaciers.”

However, the statement that “Central Mexico is home to billions of Monarch Butterflies, whose 2 year /4 generation long trip to Canada and back amazes both scientists and the general public” is misleading. First, there may be millions of Monarch Butterflies, but there are not billions. Secondly, not all Monarch Butterflies migrate. Thirdly, those that do migrate are part of an annual (1 year) cycle involving 4 or 5 generations, not a two year cycle.

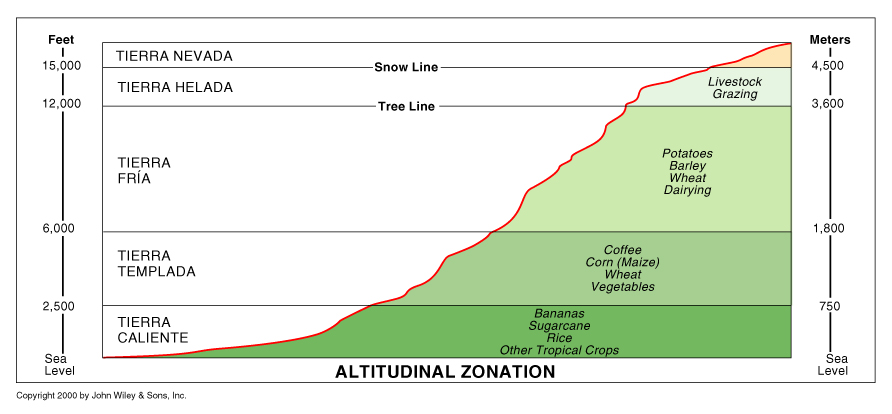

The text later claims that the Monarch Butterfly reserves “are located on old volcanic hills covered with pine-oak forest”. Actually, they overwinter in pine-fir forests. Mexico’s pine-oak woodlands occur only at much lower elevations.

The only birds incorporated into Mexico’s “biological wonders” are its pink flamingos, yet there are dozens of other bird species that are equally worthy of inclusion. Fortunately, the texts accompanying the maps of caves and cenotes (sinkholes), waterfalls, volcanoes, canyons and geologic sites appear to be much more accurate.

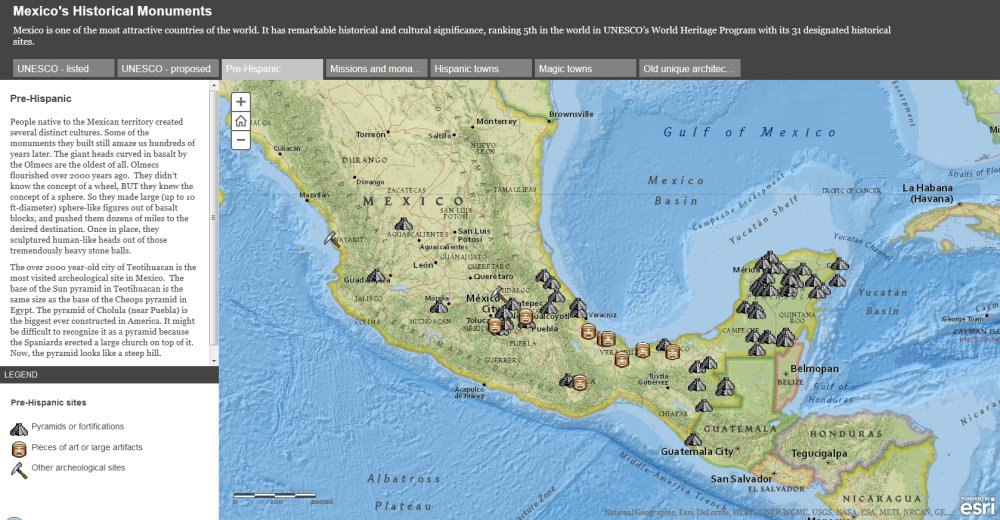

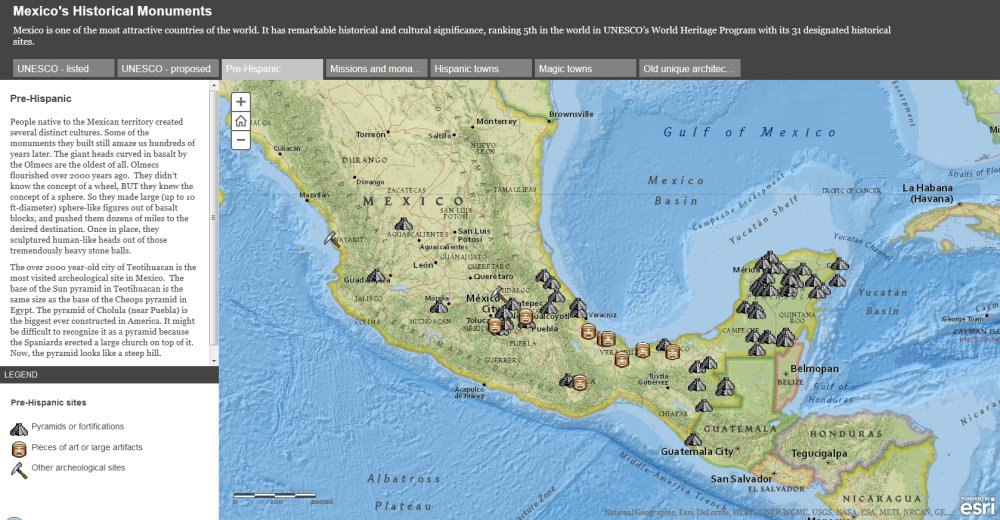

Screenshot of ESRI’s story maps of Mexico.

3. Historical monuments

This section includes a useful map of Mexico’s World Heritage sites, though absent (from both the declared sites and the proposed sites) is the El Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve in Sonora, which in June 2013 became Mexico’s 32nd World Heritage Site.

The great weakness of the maps of “archaeological sites” and “missions and monasteries” is that no clues are given as to how and why particular locations were selected for inclusion. This leads to some anomalies in the distribution. For example, Oaxaca is almost a no-show for “missions and monasteries” according to the map, despite such buildings being the subject of an excellent and extensive book by Richard Perry published as long ago as 2006, Exploring Colonial Oaxaca: The Art and Architecture.

The map of Magic Towns is also a useful map, though many more towns have been added to the list since 2012.

4. Geography of Mexico – Did You Know?

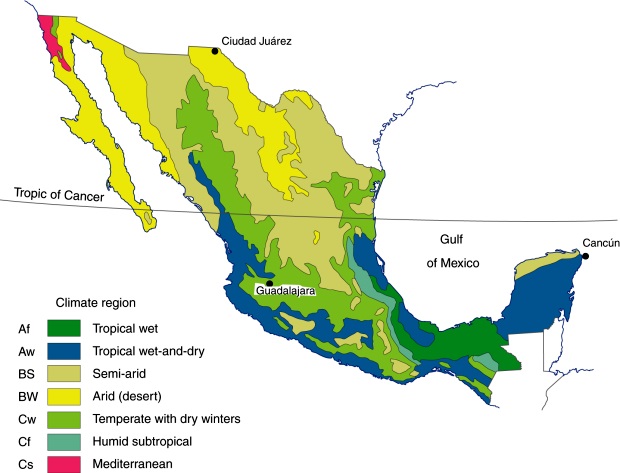

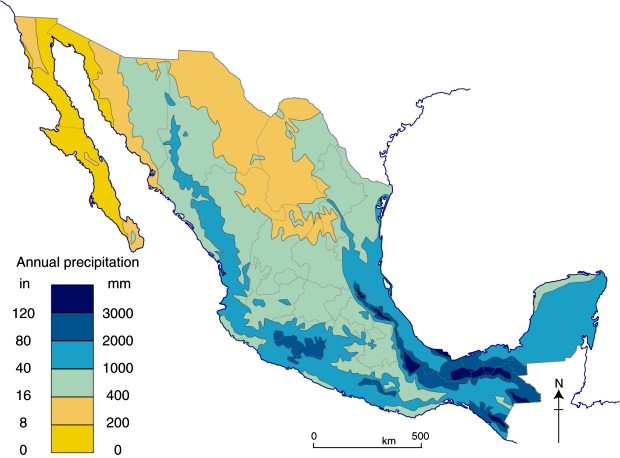

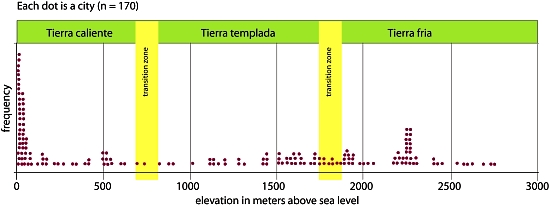

This series of maps will be quite useful to many classes as a quick way to introduce the basic physical and settlement geography of the country. Maps of relief and precipitation are accompanied by one of time zones and a simple map of states (though these are not named on the “map story” version) and major cities.

The introductory text to this section claims that “the array of Mexican volcanoes stretches along the same latitude as the volcanoes of Hawaii. Analogously, those located at the eastern ends are the newest and highest.” This may be true for Hawaii, but is not the case for Mexico. There is no simple pattern to the heights of Mexico’s major volcanoes, and certainly those in the east are not significantly younger than those in the west.

5. Indigenous People of Mexico

The single map in this section attempts to show the location of about 25 of Mexico’s many indigenous groups. The colors chosen for each group are in many cases confusingly similar, though the names of each group do appear as you zoom in on parts of the map.

The introductory text makes a strong case for Mexico’s attractiveness to tourists, yet concludes with the strange (and unanswered) question, “So why isn’t Mexico a major tourist destination?” Mexicans would beg to differ. Mexico is a major tourist destination. In 2013, for example, it received 23.7 million international visitors who spent 13.8 billion dollars. In fact, Mexico is ranked #11 in the world in terms of tourist arrivals (and that number excludes the 70 million or so border tourists each year).

6. Cartograms of Mexico

The cartograms in the last section certainly add interest to the map stories, but the basis of the “travelers attractiveness” map (those 650 tourist attractions again) means that the map is not a very good reflection of tourist numbers across the country. The significance of the State of Mexico is greatly exaggerated, while states such as Quintana Roo (with the resort of Cancún) and Baja California Sur (with Los Cabos) fail to stand out.

The final “fictional map” purports to portray Mexico as perceived by Californians. Based on the author’s personal impressions, in some ways this is the single most interesting map in the entire collection!

All in all, these maps are a mixed bag. The idea behind them is great, as is the decision to produce them in a flexible GIS system. If the details were refined a little, and more explanation offered about the basis for selecting places for inclusion, they would be even more useful in geography classes, and might go some way towards helping American students gain a better appreciation for their southern neighbor.

On the one hand, very few U.S. or Canadian universities have courses devoted specifically to Mexico. There are quite a number of geography courses with titles such as “The Geography of Mexico, the Caribbean and Central America”, or “The Geography of Latin America”, but very few that focus mainly or solely on Mexico. This is unfortunate and means that most geography students graduating from USA universities will have only a partial knowledge, at best, of their southern neighbor. It also means that Geo-Mexico was not adopted by as many university courses as we might have hoped.

On the one hand, very few U.S. or Canadian universities have courses devoted specifically to Mexico. There are quite a number of geography courses with titles such as “The Geography of Mexico, the Caribbean and Central America”, or “The Geography of Latin America”, but very few that focus mainly or solely on Mexico. This is unfortunate and means that most geography students graduating from USA universities will have only a partial knowledge, at best, of their southern neighbor. It also means that Geo-Mexico was not adopted by as many university courses as we might have hoped.