To understand the distinctive settlement patterns of the Tarahumara today, we first need to romp through a thumbnail history covering their experiences during the years following the Spanish Conquest.

While it is uncertain precisely when the Tarahumara arrived in this area, or where they came from, the archaeological evidence seems to support the view that they probably only arrived a short time before the Spanish reached the New World. By 1500 A.D., the Tarahumara had stone dwellings, simple blankets of agave fiber, stone “metates” (pestles), and combined hunting and gathering with the cultivation of corn (maize) and gourds. Settlements at this time would have been small and scattered, with no more than a few families able to survive in any given area. Then the Spanish arrived.

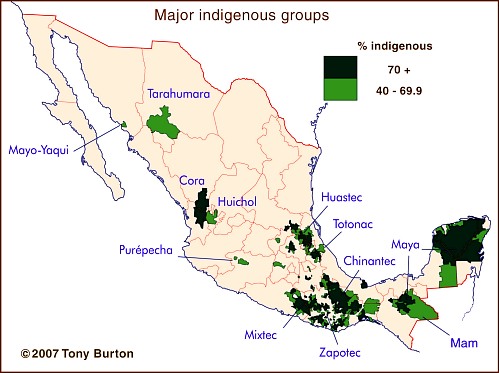

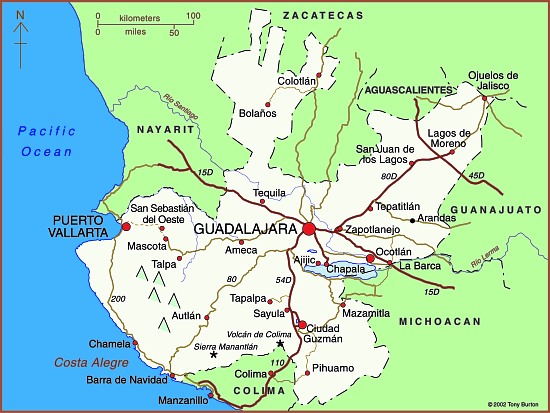

In early colonial times, Spanish explorers and clerics gradually moved ever further north of Mexico City. The first twelve Jesuits had arrived in New Spain in 1572; more arrived in 1576 and by 1580, they had already established centers for their work in Michoacán (1573), Guadalajara (1574), Oaxaca (1575), Veracruz (1578) and Puebla (1580). However, the inaccessibility of the Copper Canyon area prevented them from extending northwards as fast as they had hoped.The first important Spanish contact with the Tarahumara dates from around 1610 when a Jesuit missionary, Juan Fonte, established a mission at San Pablo de Balleza. This mission, located between the traditional territories of the Tarahumara and the neighboring Tepehuan Indians, was short-lived. In 1616, a Tepehuan‑inspired revolt led to Fonte’s death. Several hundred Spaniards along with thousands of Indians were killed in the ensuing two years of conflict.

During the remainder of the 17th century, however, the Jesuits made a steady advance, establishing numerous missions including Sisoguichi, which is still the center of their influence today. These Jesuit missions were a clerical modification of the encomienda system, an institution designed to help spread Spanish civilization, by rewarding chosen settlers with the right to collect tributes and labor from the indigenous population. The Jesuit missions usually had two friars teaching religion, handicrafts, agriculture and self‑government, together with a few soldiers for protection.

As early as 1645, some Tarahumara were working in mines, some as slaves, others voluntarily for wages. This is when both the Jesuits and the mine operators encouraged the Indians to relocate and concentrate their homes in villages or towns. This major change in settlement pattern facilitated the provision of religion and education and made it easier to organize the labor force. The Tarahumara resisted this move more strongly than other indigenous groups did elsewhere in New Spain.

The early Jesuit/Tarahumara contacts were relatively friendly, but disillusionment soon set in and around 1650 the Tarahumara essentially split into two opposing factions, the “baptizados” (Christians) and the “gentiles” (unconverted). The former decided that the priests offered a worthwhile alternative to their traditional way of life and remained in the missions. The gentiles, blaming the Spanish God for widespread epidemics, withdrew into the difficult terrain of mountains and canyons of the Copper Canyon region, effectively trying to avoid any further contact with the Spanish. Later rebellions by the gentiles , such as that in the 1690s, were brutally put down by Spanish troops. This ended Tarahumara military resistance but ensured that they withdrew still further into the canyons.

The mission settlements

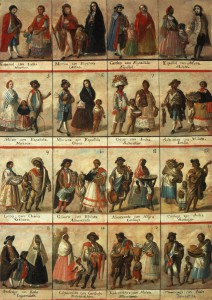

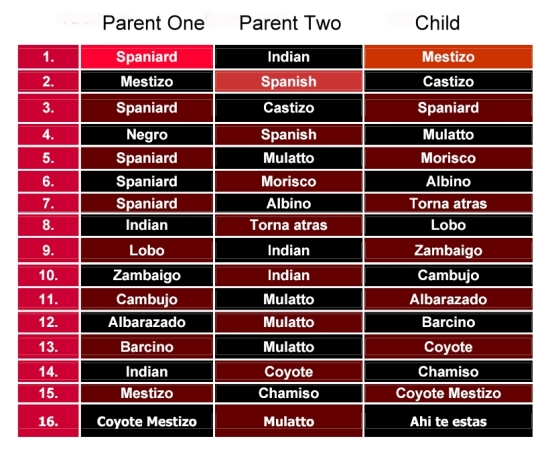

The two groups of Tarahumara now have very different settlement patterns, and some significant differences in their way of life. The baptizados live in mission villages, many of which are located east of the true canyon region, where valleys offer ample arable land and better possibilities for highways and communications. The settlements are nucleated, with homes built close to the protection of the church, and farmland surrounding the villages. These villages attracted many mestizo settlers, who saw opportunities in agriculture, forestry and commerce. Intermarriage became more common and the Tarahumara’s social customs changed as they assimilated more mestizo habits and became more Mexicanized.

The mission settlement of Cerocahui

The largest settlement in the region is Creel, a much more modern town, founded in 1906. The town received a massive boost following the completion of the railway between Creel and Chihuahua in 1907, and again in the 1960s when the “Copper Canyon” railway to Los Mochis and Topolobampo was finally completed.

Creel has also benefited in the past decade from its designation as one of Mexico’s Magic Towns and has received significant investments in tourist and urban infrastructure. Set at an elevation of 2340 m (7,600 feet) above sea level, Creel lies some distance from the nearest canyon, but has become the main marketing, lumber and tourist center and the gateway for trips into the more remote areas. Its population is about 6500.

Twenty kilometers from Creel is Cusárare (“Place of Eagles”), a typical mission village. The simple mission church, originally erected in 1767, was rebuilt in the 1970s. The village has a few small “corner” stores, some also selling tourist souvenirs. Less than an hour’s walk away is Painted Cave, a good-sized cave with pictographs said to have been left by the “Ancient Ones”. In the mid‑1890s, ethnologist Carl Lumholtz wrote that “there are no Mexicans [as opposed to Indians] living in Cusárare, nor nearby. Except for the small mining camp in the Copper Canyon, there are none for more than 50 miles to south, east or west.”

The gentiles‘ settlements

The traditional Tarahumara, the gentiles, are less Mexicanized, though they continue to use introduced crops, animals and agricultural implements acquired from the Spanish priests and settlers. Restricted to marginal land on the canyons’ rims and walls, they live in small, variable‑sized, dispersed settlements, often several hours apart by foot. This pattern is no surprise, given the extremes of topography that characterize the area, the limited technology (plow agriculture) available to them, and their need for spatial mobility to ensure access to grazing land for small herds of sheep and goats.

In these marginal areas, only small pockets of potentially arable land exist and many families have plots of land scattered about a considerable area, with several hours’ walk between plots. The population of their dispersed settlements (ranchos) is variable, depending on the available resources of land and water, on the pattern of marriages, and on the amount of inherited land in other ranchos, but averages between 2 and 5 family groups, a total of between 10 and 25 individuals.

The serious challenge is finding any land suitable for farming. Photo: Tony Burton; all rights reserved.

The homes are often perched on the gently sloping tops of the steep-sided spurs that jut out from the canyon rim, affording spectacular views, but with dangerous drop-offs beyond the areas suitable for settlement and cultivation. Individual dwellings used to be stone and mud huts, or caves in the canyon wall. The Tarahumara’s skill with the axe (a 17th century introduction) is considerable and, today, houses and other structures are made almost entirely of wood, though many caves are still inhabited, at least for part of the year. Caves which face south are preferred and their position on distant hillsides is often marked by a black, smoke‑darkened upper rim.

Perhaps the best‑built structures are their storage boxes which are wooden cubes (side about 2 m) where notched hand‑hewn planks are fitted together so tightly that not even a mouse can gain access. These structures are raised about 50 cm off the ground, usually on boulders, and have wooden roof singles. They are used to store not only food but also animal hides, horsehair ropes, simple implements, cloth, yarn and anything considered valuable. Where wood is harder to obtain, they are built of stones and mud.

Their houses are constructed in a similar fashion, but with less attention to detail. Their houses are not, therefore, very permanent. Indeed, one ancient Indian tradition holds that when a member of the household dies, the house should be abandoned or destroyed. Nowadays, the family simply moves the structure a few hundred meters and rebuilds it. The houses have dirt floors and minimal furnishings, such as wooden benches and stumps, items for food preparation, metal plates and a bucket and some animal (goat or cow) skins for sleeping on. There may also be some rough blankets and a homemade violin.

Most gentiles have more than one dwelling since they wander far afield with their animals in search of pasture and food, and since many practice a form of transhumance, spending winters near the canyon floor and summers near the canyon rim.

Sources / Bibliography:

- Bennett, W. and Zingg, R. (1935) The Tarahumara. Univ. of Chicago Press. Reprinted by Rio Grande Press, 1976. Classic anthropological work.

- Dunne, P.M. (1948) Early Jesuit Missions in Tarahumara. Univ. Calif. Press.

- Kennedy, J.G. (1978) Tarahumara of the Sierra Madre; Beer, Ecology and Social Organization, AHM Publishing Corp, Arlington Heights, Illinois. Republished, as The Tarahumara of the Sierra Madre: Survivors on the Canyon’s Edge in 1996. This anthropologist lived in one of the more remote Tarahumara areas for several months, accompanied by his wife and infant daughter.

- Lumholtz, C. (1902) Unknown Mexico. 2 volumes. Scribner’s Sons, New York. Republished in both English and Spanish, this is a fascinating ethnographic account dating back to the end of the 19th century.

- Pennington, C. (1963) The Tarahumar of Mexico, their environment and material culture. Univ. of Utah Press. The reprint by Editorial Agata, Guadalajara, 1996, of this classic account of Tarahumara life and culture is embellished with wonderful color photographs, taken by Luis Verplancken, S.J. (1926-2004), who ran the mission in Creel for many years.

Related posts: