The Consejo Ciudadano para la Seguridad Pública y la Justicia Penal AC, a Mexican non-profit, has published an interesting report looking at the levels of violent crime in Mexico in 2013:

The authors take violent crimes to include intentional homicide, kidnapping, rape, aggravated assault, robbery with violence and extortion.

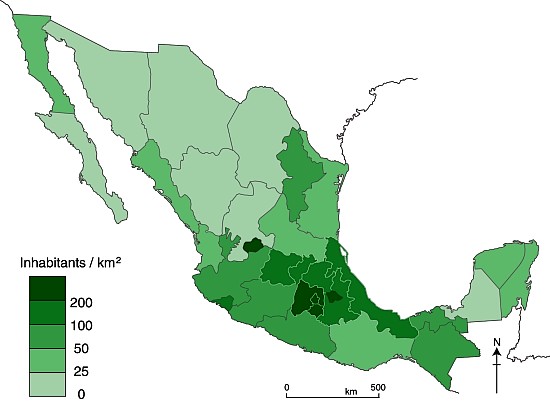

At the municipal level, violent crime is concentrated in a relatively small number of municipalities. The report looks at the statistics for the 216 municipalities (including delegaciones of the Federal District) that had estimated populations of over 100,000 in 2013. Since 2012, four municipalities have joined this group: El Fuerte (Sinaloa), Tepotzotlán (México), Pánuco (Veracruz) y Playas de Rosarito (Baja California). Between them, the 216 municipalities are home to about 64% of Mexico’s total population.

Data from government agencies and INEGI were used to compile rates for each crime in each municipality. These rates were then multiplied by the following weightings (to reflect the relative severity and impacts of each type of crime),

- 0.55 for intentional homicide

- 0.22 for kidnapping

- 0.13 for rape

- 0.04 for aggravated assault

- 0.03 for robbery with violence

- 0.03 for extortion

and summed to give an overall index for “violent crimes”. For the 231 municipalities, the index ranged from 106.63 for Oaxaca, Oaxaca to 0.00 for Zapotlán el Grande in Jalisco. The full details of the methodology are explained and discussed in the report. A similar methodology was also used to calculate levels of violence by state.

The worst 10 municipalities in terms of violent crime were:

- Oaxaca, Oaxaca – violent crime index value of 106.63

- Acapulco, Guerrero – 80.35

- Cuernavaca, Morelos – 65.30

- Yautepec, Morelos – 56.19

- San Pedro, Coahuila – 53.42

- Cd. Victoria, Tamaulipas – 52.48

- Iguala de la Independencia, Guerrero – 52.25

- El Fuerte, Sinaloa – 50.82

- Jiutepec, Morelos – 50.29

- Torreón, Coahuila – 49.31

The national index (ie treating the entire country as a single entity) was 23.17, meaning that the index value for violent crimes in Oaxaca, Oaxaca, was more than four times that of the country as a whole.

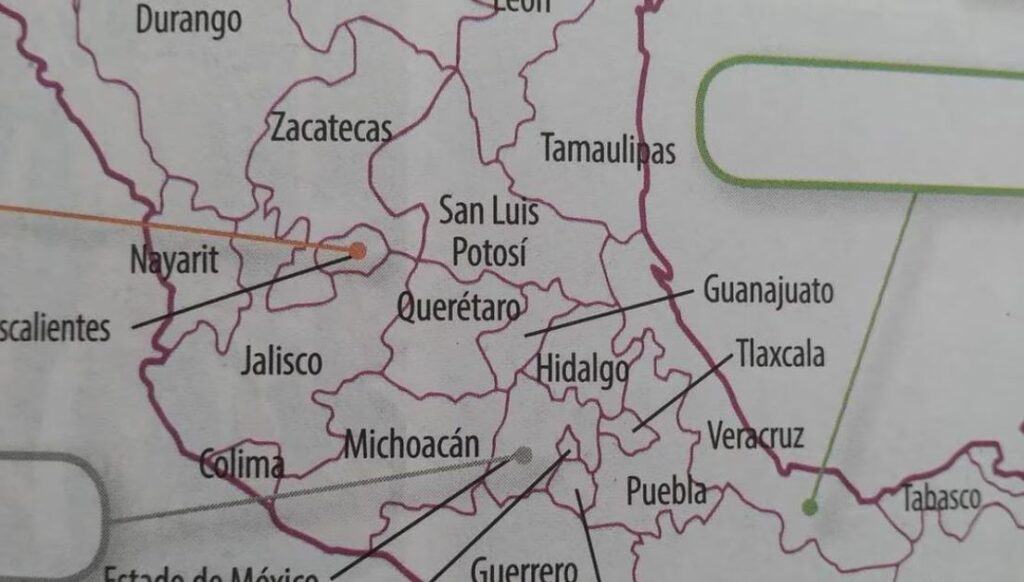

Municipalities which were in the worst twenty in 2012 for violent crime, but have now fallen out of that group include: Lerdo (Durango) Zacatecas (Zacatecas), Cuautla (Morelos), Zihuatanejo (Guerrero), Temixco (Morelos), Cuauhtémoc (DF), Tecomán (Colima), Navolato (Sinaloa), Centro (Tabasco) and Monterrey (Nuevo León).

Moving into the worst twenty for the first time are: Playas de Rosarito (Baja California), Hidalgo del Parral (Chihuahua) San Pedro (Coahuila), Chilpancingo (Guerrero), El Fuerte (Sinaloa) and Chalco, Cuautitlán, Cuautitlán Izcalli, Ecatepec and Naucalpan (all in the State of Mexico).

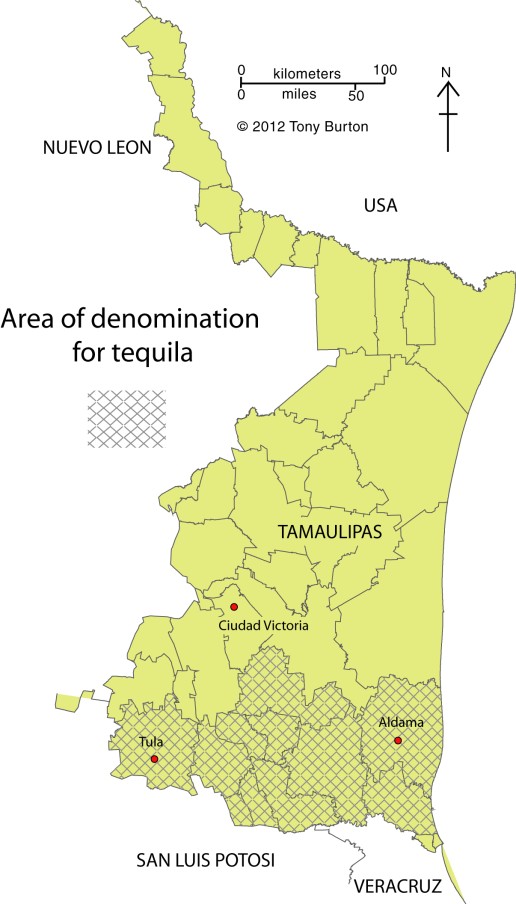

Of the 213 municipalities, Acapulco had the highest intentional homicide rate (112.81/100,000, about 6 times the national rate of 19.05/100,000). Cd Victoria had the highest kidnapping rate (23.28/100,000, 15 times higher than the national rate of 1.46/100,000, though kidnapping rates in Mexico are notoriously unreliable, and have been the subject of intense press debate in recent months).

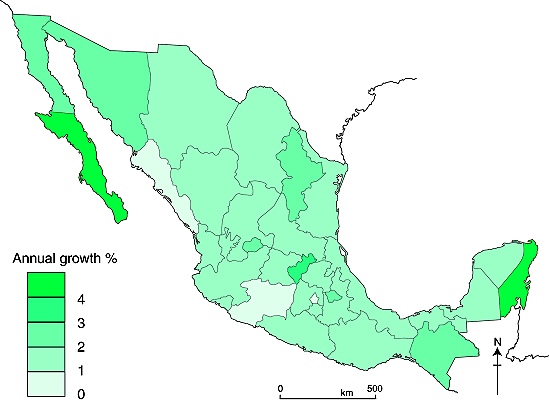

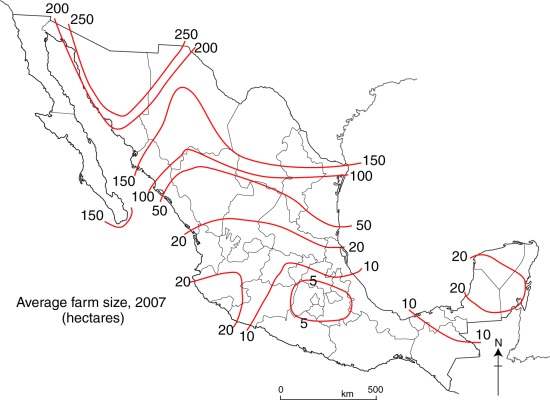

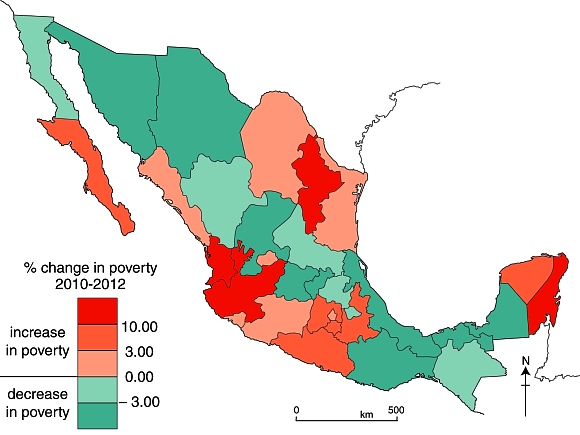

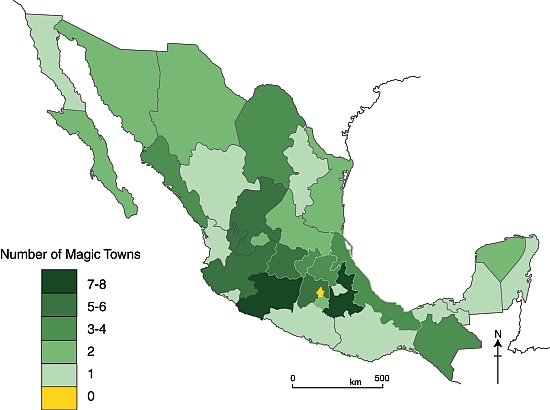

Violent crimes by state, 2013

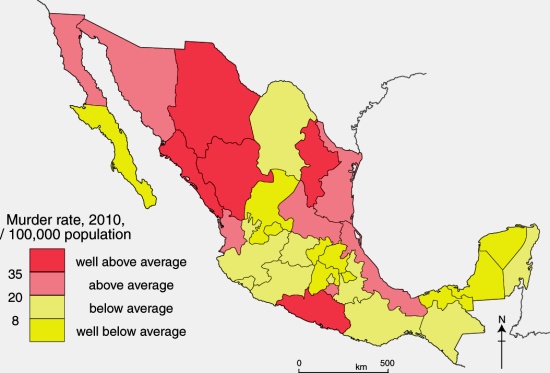

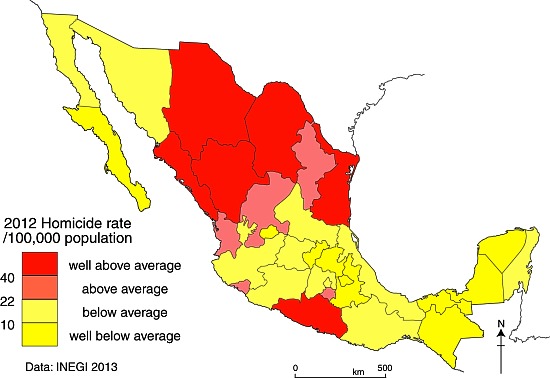

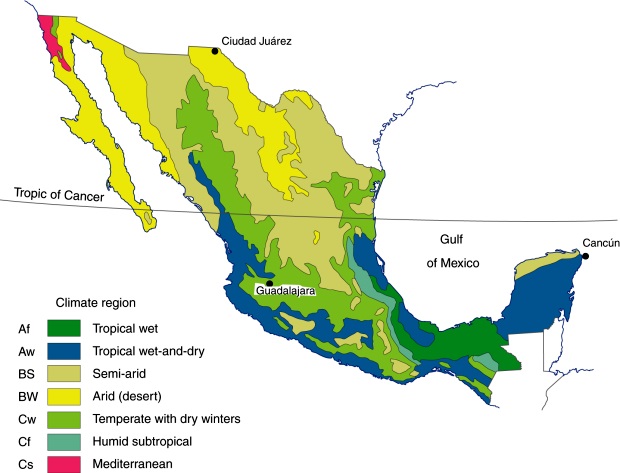

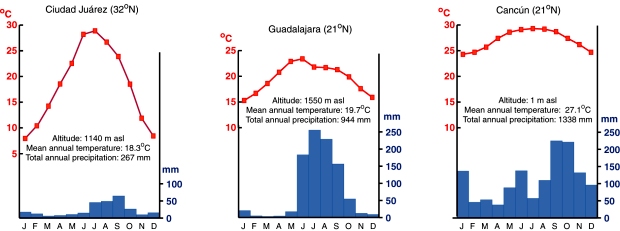

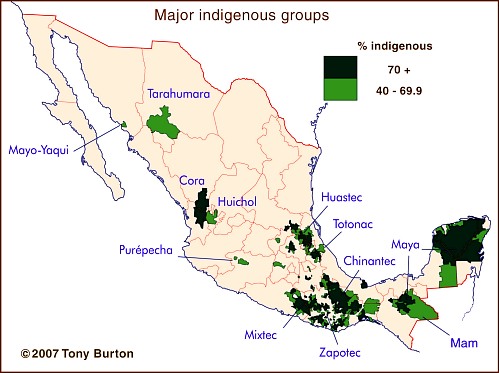

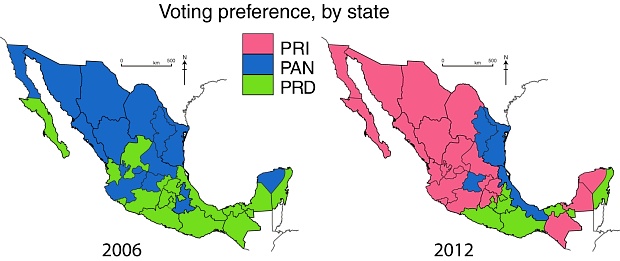

By state (see map), Guerrero had the highest violent crime index with 47.76 points, followed by Morelos 43.99 and Chihuahua 40.87. In general, with the prominent exceptions of the State of México and Guerrero, the southern half of Mexico appears to be somewhat safer than the northern half.

Violent crime index, 2013. Source of data: see post. Credit: Geo-Mexico

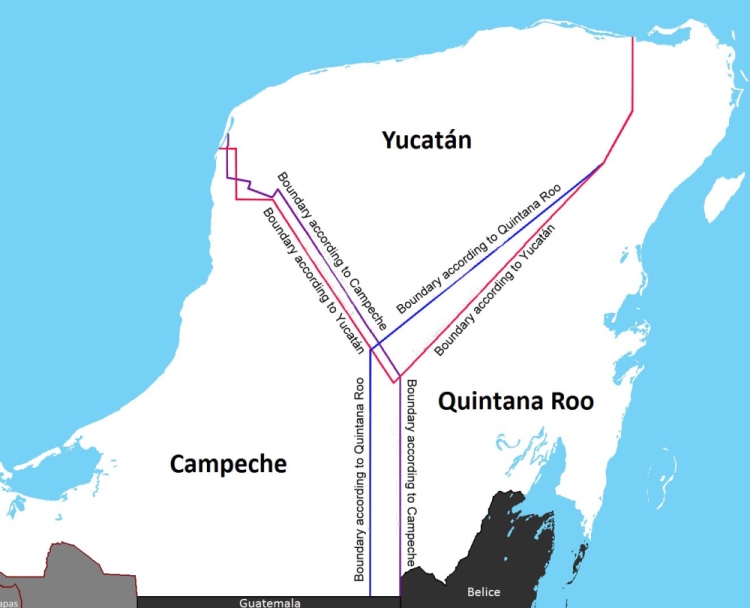

For individual categories of crime at the state scale, Morelos had the highest kidnapping rate (8.24/100,000). Quintana Roo had the highest rate of rape (28.31/100,000, compared to national average of 11.36/100,000). The State of Mexico had the highest rate for aggravated assault (251.64/100,000 compared to national average of 130.21/100,000). Morelos came out on top for the highest rate of robbery with violence (455.08/100,000 compared to national average of 182.61) and for the highest rate of extortion (21.96/100,000 compared to national average of 6.94/100,000).

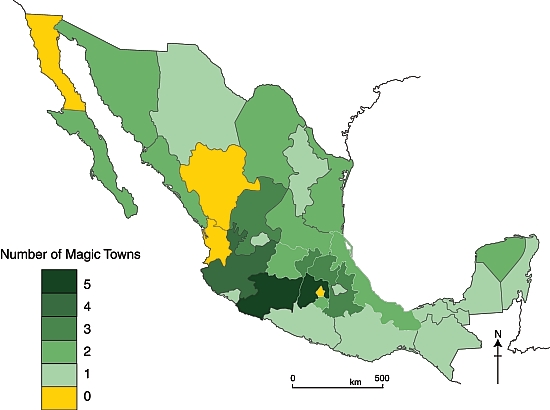

Good news for tourists

According to this report, almost all of Mexico’s major tourist destinations (with the noteworthy exception of Acapulco) are located in areas where violent crime is below the national average.

Related posts:

Click for printable pdf map

Click for printable pdf map