Mexico is the world’s leading producer of silver and has occupied top spot for several years. Mexico’s output of silver rose 2.0% in 2015 to 5,372 metric tons (189.5 million ounces). Mexico is responsible for 21% of global production, followed by Peru (15%), China (12%) and Australia and Russia (each 6%). About 70% of silver produced in Mexico is exported, the remainder is sold on the domestic market.

Global silver production fell slightly in 2015 due to decreased output from Canada, Australia and China. World demand for silver in 2015 reached a record 33,170 tons (1,170 million ounces), due to surges in three manufacturing sectors: jewelry, ingots and coins, and photo-voltaic solar panels.

The increased output in Mexico came from expansions in the Saucito and Saucito II mines, operated by Fresnillo, and the El Cubo mine, managed by Canadian firm, Endeavour Silver. A similar increase in production is predicted this year, given the on-going expansion of the San José mine, owned by Canada-based Fortuna Silver Mines.

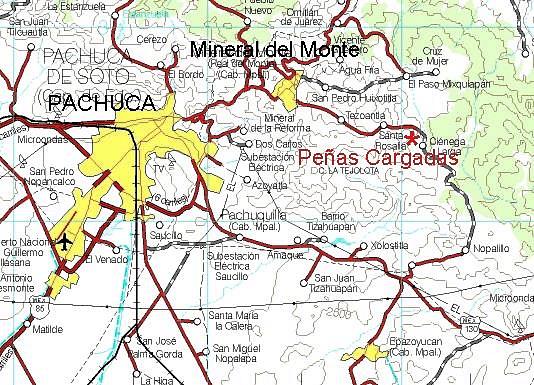

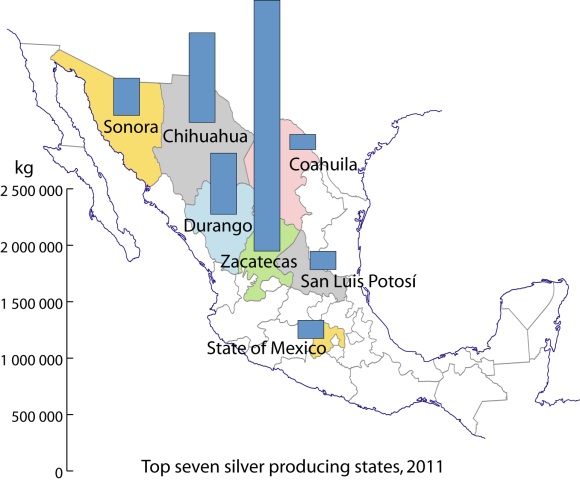

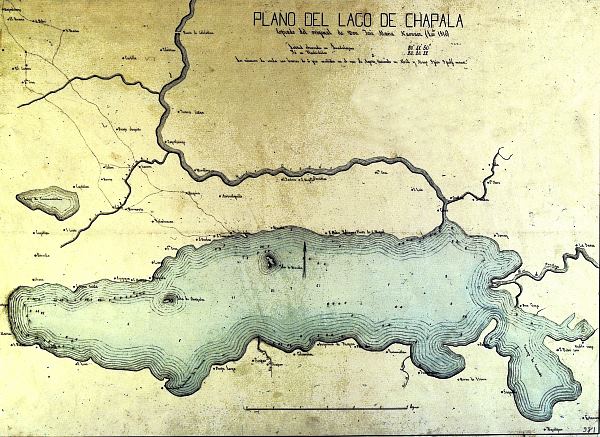

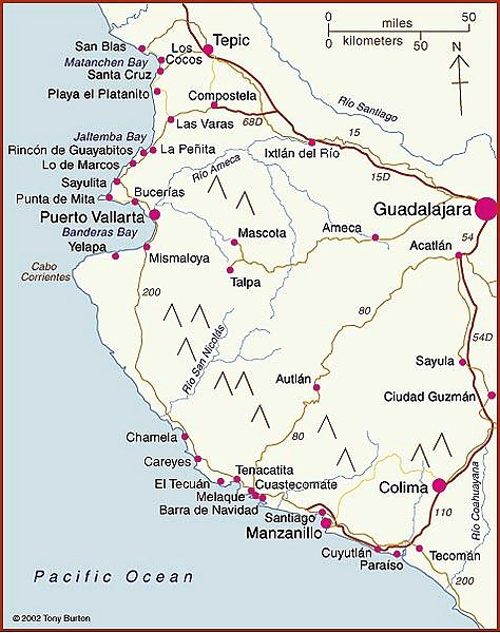

Zacatecas is Mexico’s leading silver producing state (46.5% of total; see map), well ahead of Chihuahua (16.6%), Durango (11.3%) and Sonora (6.9%).

In Zacatecas, silver mining is especially important in the municipalities of Fresnillo (24% of total national silver production) and Mazapil (15%) as well as Chalchihuites and Sombrerete (3% each). The main silver mining municipality in Chihuahua is Santa Bárbara (3% of national total). In Durango, San Dimas and Guanaceví are each responsible for about 3% of national production, while the leading municipality for silver in Sonora is Nacozari de García (1%).

The legacy of silver

The importance of silver mining in colonial New Spain can not be over-emphasized. For instance, during colonial times nearly one third of all the silver mined in the world came from the Guanajuato region!

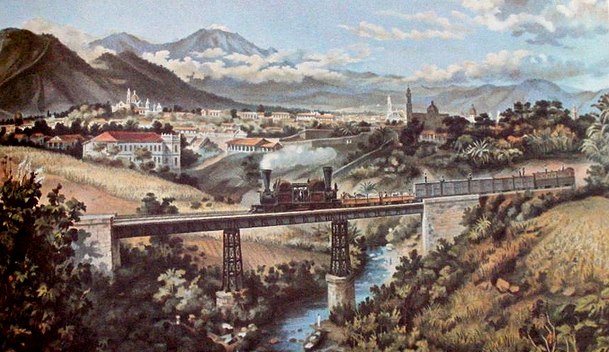

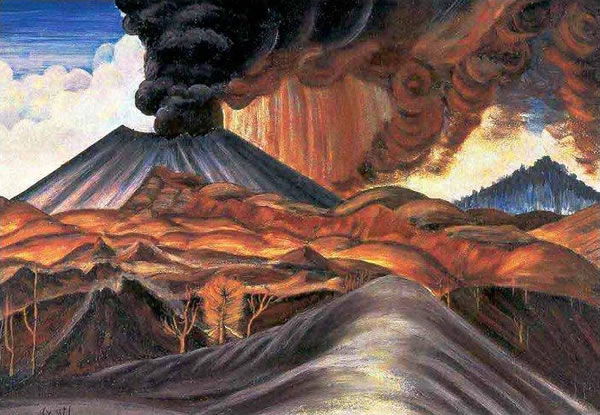

Even today, the cities and landscapes of many parts of central and northern Mexico reveal the historical significance of silver mining. The legacies of silver mining include not only the opulent colonial buildings in numerous major cities such as Zacatecas and Guanajuato, as well as innumerable smaller towns, but also the deforestation of huge swathes of countryside.

The landscape of states like San Luis Potosí, Zacatecas and Guanajuato was forever changed by the frenzied exploitation of their woodlands. Silver mines needed wooden ladders and pit props. The smelting of silver ore required vast quantities of firewood. Barren tracts of upland testify to the success of those early silver mines. Mining played a crucial role in the pattern of settlement and communications of most of northern Mexico. The need to transfer valuable silver bullion safely from mine to mint required the construction of faster and shorter routes (see, for example, El Camino Real or Royal Road, the spine of the colonial road system in New Spain), helping to focus the pattern of road and rail communications on a limited number of major cities.

Once workable ores ran out, smaller mining communities fell into obscurity and many became ghost towns. Some of these settlements, such as Real de Catorce and Angangueo, have enjoyed a new lease of life in recent years due to tourism.

The main town associated with silver and tourism is Taxco, the center of silversmiths and silver working in Mexico.

Mining towns described briefly previously on Geo-Mexico.com include:

- Fresnillo, Mexico’s leading silver mining town

- Mapimí (Durango)

- Batopilas (Chihauahua)

- Pinos (Zacatecas)

- Angangueo (Michoacán)

- Sombrerete (Zacatecas)

- Mineral de Pozos (Guanajuato)

- San Sebastián del Oeste (Jalisco)

Note: This is a 2016 update of a post first published in 2013.

Related posts:

![Towns, by state (September 2015) [corrected]](http://geo-mexico.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/magic-towns-sep-2015-corrected.jpg)